|

On Beauty |

|

In the first stage of My

Nefertiti, certain spatial relationships in the composition need to be

addressed. So I decided to start a new stage in order to achieve what I

want. In the final stage the straight at the base of the fingers is

produced to form the straight denoting the arm- pit

area. Finally, the straight forming the lower edge of the arm is produced

to form the base for the shiny part of the hair. The curves appearing in

the composition in the breast and elsewhere have the

curvatures of perfect circles or coils. In the first stage of My

Nefertiti, certain spatial relationships in the composition need to be

addressed. So I decided to start a new stage in order to achieve what I

want. In the final stage the straight at the base of the fingers is

produced to form the straight denoting the arm- pit

area. Finally, the straight forming the lower edge of the arm is produced

to form the base for the shiny part of the hair. The curves appearing in

the composition in the breast and elsewhere have the

curvatures of perfect circles or coils. |

Unfortunately, the second

stage of My Nefertiti is not a good resolution either. It does not

show

the specific facial features that I want what is essentially an imagined

Egyptian beauty to assume.

Finally, the third and final stage yields a portrait that even the great

Titian would smile. Unfortunately, the second

stage of My Nefertiti is not a good resolution either. It does not

show

the specific facial features that I want what is essentially an imagined

Egyptian beauty to assume.

Finally, the third and final stage yields a portrait that even the great

Titian would smile.

In this composition may be

found a complex system of supreme spatial relationships, each facet or

fragment of which is designed to

give rise to great visual

pleasure.

Visual pleasure arises

out of the actualization of the supreme mathematical relationship from

which we derive the notion of the sublime. When Einstein looked at

certain mathematical relationships found in the universe, he exclaimed

that he had seen the hand of the Creator in it. Likewise,

Shroedinger, under a similar circumstance, proclaimed that we (i.e. the

transient beings) are actually God Almighty Himself. Those mystics of

scientists were able to see what Buddha saw at his moment of enlightenment

under a tree. This seeing makes each of them the Buddha.

The goal of a viewer is to

examine the work’s vitality, movement, integrity in their calligraphic and

poetic elements. To detect those dynamics in a masterfully executed

painting, we must look at art intently. We must look at it and look at it

until it “speaks” to us in our native tongues, calling us each tenderly by

our names. Seeing beauty until we “swoon into our own dying” (quoting Ken

Wilber). Formal transfiguration in great art is what imparts life to the

work. That is what makes the art so timelessly engaging. That

transfiguration which also transforms the viewer. |

|

|

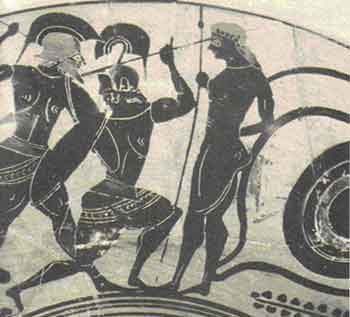

Figure 19: Ben Lau “Dispute”

linoleum cut

In the above composition,

the compactness of forms is not just evident in the individual animal

configuration but also throughout the entire structure of the composition.

The “ring formed of the bodies of the three animals is as solidly grounded

as that formed in the “ring” of the dancers in Matisse’s “Dance”. An

elaborate geometric groundwork has made this compactness possible.

Until one has learnt how to

look, the vicious cycle of getting fooled would never, ever be broken!

Ben Lau Spring 2005

|